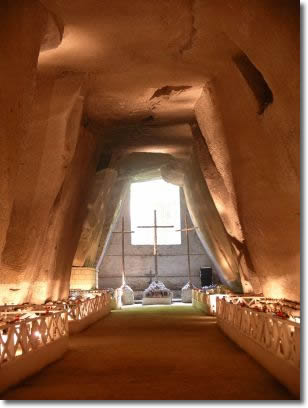

The Cemetery of the Fontanelle

- Interior of the Cemetery of the Fontanelle

From the hills today called the "Colli Aminei" there used to run four impluvia which, cutting into the tufo, brought it to the surface, so creating gorges through which ran the so-called "Virgins' Lava", a mixture of mud and debris that derived from the erosion of the pyroclastic blanket that covers the surrounding hills.

Over thousands of years, the "virgins' lava" eroded the gorge of the Fontanelle of the Sanità area, creating optimal conditions for the extraction of tufo which the laws of the 17th century, the customs of the time, forbade the digging of "intra moenia" (within the walls), so that it was extracted "extra moenia" (outside the walls) in this area. The street named Via Fontanelle follows the course of the oldimpluvium on whose banks there are numerous caves which, until the 19th century, provided the building material for the building activities of the whole city and which are today used for various purposes: olive warehouses, glassworks, chocolate factories, marble, garages and wine cellars.

Praus that even at that time the Fontanelle were worked by gravediggers. At that time dead bodies were buried in the churches, but there was no lober any room , so the gravediggers dug them up at night and put them in the old abandoned caves. Following one of the many floods, many bodies were carried out of the caves and it is said that the inhabitants of the Sanità dare not leave their houses for fear of recognising their long-dead relatives. The gravediggers were therefore ordered to arrange the dead bodies in the last of the caves.

The origin of this ossuary, however, goes back to the 16th century when the city underwent three people's revolts, three famines, three earthquakes, five eruptions of Vesuvius and three epidemics; so, this being an isolated place, it was used to collect the corpses of the victims. The plague of 1656 was disastrous, so that the walls of the caves were knocked down again and many think that the caves themselves contained 250,000 corpses of a total population of 400,000, while others think they were as many as 300,000. The architect Carlo Praus recounts that in 1764, "a time to remember as one of a terrible famine", the Cemetery of the Fontanelle was used by the Public Health Committee to bury the bodies of the poorest members of the population for which there was no room in the public burial grounds of the churches in the City. Following the edict of Saint-Cloud of June 1804, in 1810 Praus produced plan for the construction of a vast burial ground by extending the ancient necropolis of the Fontanelle.

In 1837, the Health Council ordered other bodies to be taken to the cemetery after the outbreak of "colera morbu". In the same year, with the order to remove all the bones from all the cemeteries of the parishes and the confraternities and to transport them to the Fontanelle Ossuary, a large number of carts, accompanied by monks and guards, took the mortal remains to the caves and heaped them up there. The cemetery was left in a state of abandon until 1872, when the parish priest of the church of Materdei, Don Gaetano Barbati, called on the people of the area to help him put some order into the bones, and that is how they are to be seen today, all anonymous except for two skeletons, those of Filippo Carafa Count of Cereto of the Dukes of Madaloni, who died on 17 July 1797, and Donna Margherita Petrucci, maiden name Azzoni, who died on 5 October 1795. Both restin coffins protected by glass.

The corpse of Donna Margherita is mummified and the skull has a wide open mouth as if about to vomit, and for this reason it is said that the noblewoman died of choking on a piece of gnocchi. When the bones were put in order, those of the parish priests and of the members of the nave"; the central nave was called the "nave of the plague victims" because these were buried there. The last one is the "nave of the beggars" because the very poor are buried there. And so the cemetery became part of Neapolitan custom and legend. Today it is both a place of worship and of macabre fascination surrounded by legends and accounts of miracles.