- Neapolis and its area

The archaeological survey carried out at Castel Nuovo, apart from providing us with important information on the castle of the Angevin period, reproposes the issue of the topography of the area in Graeco-Roman times.

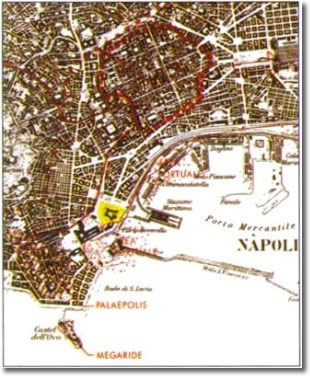

The monument stands on the coastal strip from Parthenope to Neapolis. The latter, which was founded in about 470 BC, stretches from that part of the historical centre bordered by via Foria to the north, Corso Umberto to the south, via Carbonara to the east, and via Costantinopoli to the west. Well-known aspects of this are the urban layout, a unique example of the Greek road network surviving in the present-day network, and the main chronological stages.

The layout of the Parthenope settlement isn't as well known. It was founded by the Calcidese of Cuma and was part of that town's expansion policy which, from the mid-7th century BC at least, comprehended the gulf of Naples with the creation of the port. The site is placed on the promontory of Pizzofalcone, which corresponds to the basic needs of an archaic settlement used as a trading centre. From the very beginning, the port had to be a simple landingplace situated in the costal bight to the east of Pizzofalcone in the area now occupied by piazza Municipio and piazza Plebiscito. Literary tradition associates it with the tomb and place of worship of the Parthenope siren. The same port, perhaps, continued to be used in relationship with Neapolis, though another landingplace is thought to exist further to the east, in correspondence to where via Mezzocannone begins.

The archeological data relative to Parthenope are not much, and those that exist come from chance findings. A necropolis datable from the middle of the 7th to the 9th century BC has been discovered in via Nicotera. Associated with the road joining Neapolis to Parthenope are the tombs discovered in piazza Carità, via S. Tommaso d'Aquino, via S. Giorgio dei Genovesi, via S. Giacomo, via G. Verdi, piazza Municipio and the Royal Palace. We have no knowledge of how far these graveyard areas extend, nor their exact chronology.

The repository tomb in via S. Tommaso d'Aquino definitely dates from the end of the 5th century BC, while another graveyard nucleus datable in the 5th century BC, is the one discovered at the end of the last century near the town hall. One thing that should be recorded as belonging to Parthenope is the ceramics dump generically dated in Archaic Age which was discovered in via Chiatamone to where it had drifted down from the hill of Pizzofalcone. Finally, of exceptional interest is the discovery made in via S. Giacomo, near the town hall, of a tuff-block wall of the 6th century BC, knocked down in the 4th century BC, in which the archeologists who excavated it recognise a preparation of the port which may have served as a boundary and defence.

Evidences from the archaic period can be put at the side of those of the Roman period, which coincide with the villa of L. Licinio Lucullo, the so-called "Lucullanum", one of the sumptuous residences which from the end of the Republican period occupied the western coastline of the gulf of Naples. This villa is of considerable extension, to the point that, according to some, it stretches from Pizzofalcone and Castel dell'Ovo (the ancient Megaride) to the area of the Castel Nuovo. The monuments discovered at the beginning of the present century in via S. Lucia belong to this villa. Other remains have recently been identified in the area of Castel dell'Ovo where underwater archeological investigations have revealed constructions of the imperial period submerged by descending bradyseism.